It’s Art if I say so

By Bev Dalton

It’s Art if I say so

By Bev Dalton

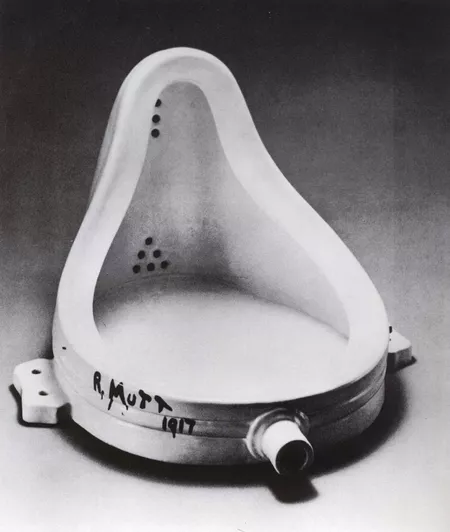

Marcel Duchamp said this: it’s art if I say so. He’s the guy who stuck a urinal on the wall and called it ‘Fountain’. And ever since he did that, the art world swivelled on its axis and became a place where apparently anything goes. And usually for a gazillion quid. Which really gets the goat of your average person on the street.

How many times have you heard someone look at a pice of contemporary art and say, ‘my kid could paint that’ ? And, you know, it’s hard to argue with that kind of logic. Because I’m an artist and sometimes even I look at stuff and think, ‘seriously?’

But I’ve come to believe it’s not art that’s the problem but the language we use to describe it.

Take music. We have composers, performers, classical artists, opera singers, pop musicians, tribute bands, and me singing along to the radio in my flat when the neighbours are out. We differentiate, for instance, between the people who wrote the songs (one particular skill set) and those that performed the songs (an entirely different skill set).

We also have labels for different styles of music, and recognise distinct levels of complexity. We don’t compare Mozart to someone singing Abba on a karaoke night down the local pub. Nor do we think that our darling eight-year-old’s new-found skills on the recorder is on same level as a concert by Lady Gaga. Yet all of these things come under the banner of music.

So, we have a language that separates composer from performer, and Country and Western star from Rapper or DJ. When it comes to music we have all the words.

But when it comes to art we have, er, artist. Yeah. That’s about it. And I think it may be this lack of language that stops us appreciating what goes into the making of Contemporary or Modern Art.

The title we give someone who creates something never before seen (think Picasso, for instance) is artist. The person who draws a fairly decent horse that is coped from a photograph is called the same. Nothing separates the person who created a new way of looking at something from the person who competently copied a Disney character onto their child’s birthday card. They are both just artists.

Therefore, we have no title that specifically acknowledges someone whose mastery of the craft, and creative genius, has revolutionised how we see things for generations to come.

So, let me introduce the idea that photography changed that art world more than any other invention.

Before photography, a large part of the art world was about getting someone to recreate an accurate (and preferably flattering) image of something or someone that already existed. The people with money wanted to show off their beautiful houses, their trophy wives, their perfect children. And who can blame them?

But once photography really took hold, this act of accurate representation was more clearly accomplished by the new media.

And art was finally free to be something else entirely.

It had always sneaked in under the radar, of course. Art was always about how the artist perceived their subject, and what they chose to show or not show. Hence a Goya looks nothing like a Renoir.

But they’d still had to pay the rent, so they’d still had to paint what the rich people wanted to hang on their walls.

Now, suddenly, art could be about ideas, thoughts, feelings, protest, and significance. Art could be an expression of what the artist wanted to say. It finally got to catch up with how music had been all along.

I’ll give you an example of how this way of thinking about art works, from my own experience.

I’m old, so I was raised in the 1970’s, where the pinnacle of art was still seen as being able to represent something as finely as a photograph. Landscapes, still lives, portraiture – these were the pillars of my learning about art.

But I finally got to study art at university when I was in my late fifties, and oh boy had it changed. I pretty much had to un-learn everything I thought I knew and start over.

But I did the work and for my degree show I became fascinated by the subject of colour. I’m slightly obsessed with colour actually. I may even be a borderline tetrachromat, which is a person with extra senses of colour. Bluntly put, I’m the annoying person who will argue with you about whether that wall is a greeny-blue or a bluey-green. I’ve always had the motto, ‘why use five colours when fifty will do‘. And I wanted to explore that a bit more.

I thought about how colour works when it’s made with pigment on a canvas surface. Light lands on the painted surface, where some of the spectrum is absorbed. What is left was bounces back into our eyes. So, a pigment that absorbs everything but the yellow part of the spectrum will appear yellow to us. This is what’s known as a subtractive system: the surface subtracts everything but the colour we perceive.

But these days we spend a lot of time looking at screens. And they use an additive system, where different coloured light is projected directly into our eyes.

This explains why the colours on our digital photos looks lovely and bright on our screens (additive system) but look a bit dull and somewhat different in hue when we get them printed out (subtractive system).

For me, the interest was in how – after all these centuries of seeing images a certain way – we were handing over our control of colour to machines and their use of the additive system.

What kind of art would a computer make, I wondered? Not just art that I tell it to make, by feeding stuff into AI and seeing what it produces. But how would a computer ‘see’ art?

Computers run by numbers. Numbers are God. And what is the most important number of all? Pi. The never-ending number. They say that every combination of numbers possible appears in Pi at some point.

And this is where I show you why I am an artist and your kid could not do this (although they could probably draw a far better unicorn than I could, you’ll get no arguments from me there).

The art piece I wanted to create had to show that transition from subtractive to additive. It had to propose the idea of us relinquishing control of colour to computers. It had to stimulate people to think about how they felt about that. It needed to make them question if this was a good thing or not.

As an artist, it was now my job to translate all this as successfully as possible.

This is where it gets complicated, so bear with me here.

Computers can’t work in decimal (base 10) cos it just doesn’t cut it, apparently. So computers use base 16, or hexadecimal. You don’t have to know any hexadecimal (which includes numbers and letters) so don’t worry about that. Suffice it to say that there are websites that work out that stuff for you. And so it was that I got the first few pages of Pi changed into hexadecimal.

Right, so now I had the God number, and I had it in a language that computers understood. Now I had to turn it into Art.

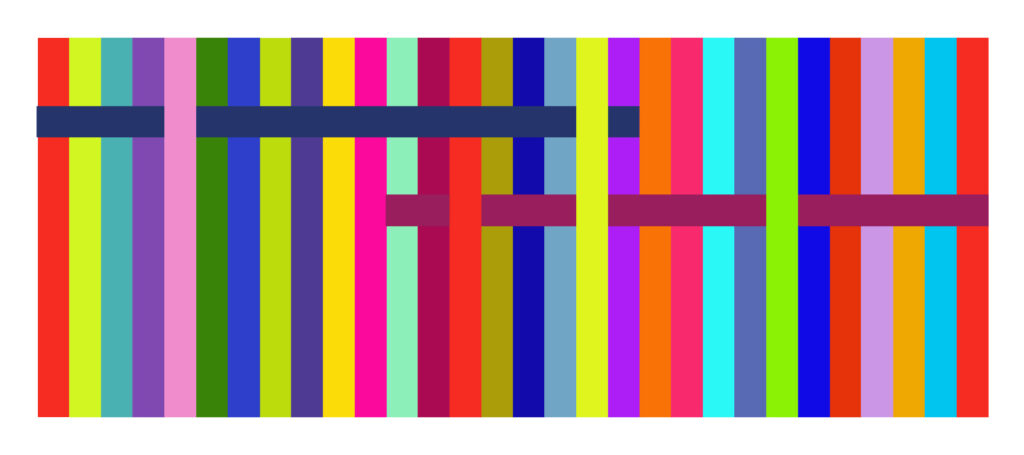

So, the first six digits of hexadecimal Pi would correspond to the code for a colour in photoshop. It’s a dark greeny-blue. The next six digits make a mauvey-grey. And so on.

For this piece to deliver its message I had to give total control to the machines. And yes, that did feel very much like I was letting the Terminator loose, but what can you do – this is art.

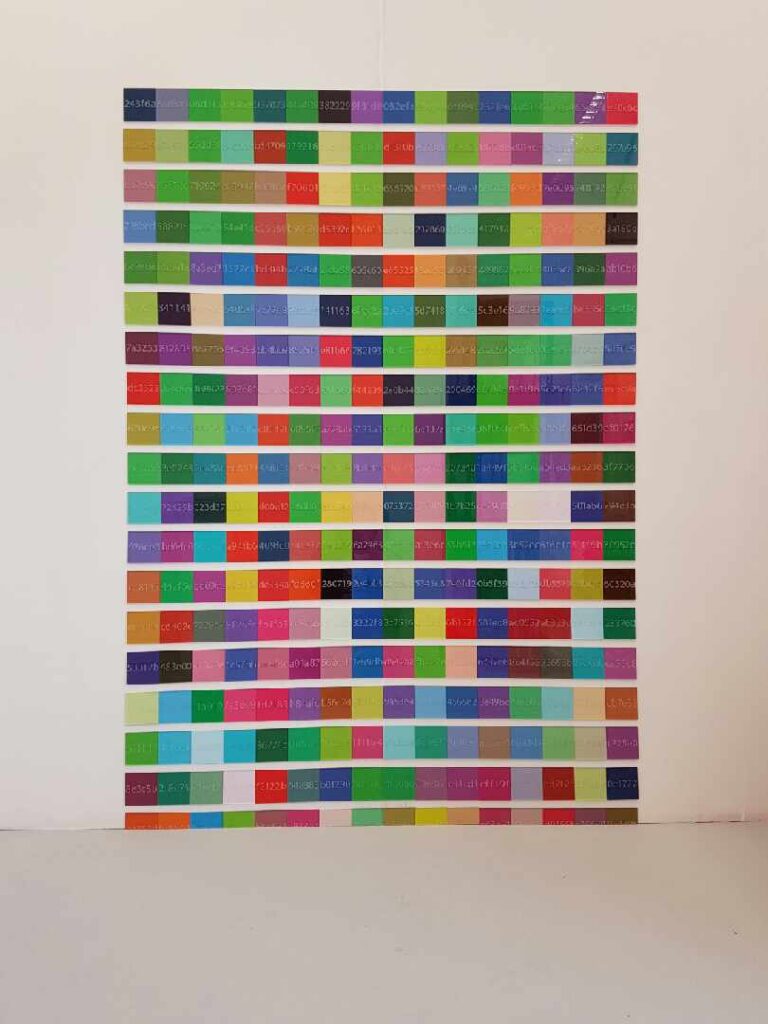

So, the finished design was made of squares (to mimic pixels) that were arranged in rows of 16 (to echo the hexadecimal theme).

I made each square out of clear perspex, in which the 6-digit code of its colour was engraved onto the surface with a CNC router. This meant I had little to do with the construction (computers were the boss again) and it had a tactile quality that referenced touch-screens.

A computer was used to colour nearly 900 squares with the correct colours, which were then printed out by another machine.

And then I spent nearly two weeks just sticking the right box of colour to the right piece of routed perspex, and tried not to go wrong too many times.

Then (and this was the hard bit) I had to stick them in rows according to how Pi dictated. And I can’t tell you how often I wanted to swap the colours around to make it ‘nice’. But I didn’t. This, after all, was part of the deal. Relinquishing control. Giving it to computers. And seeing how I felt about it.

This was exactly what I was trying to represent.

Anyway, the whole thing came out several metres high, and I had it disappearing into the ground by making the bottom row half-sized squares.

Is it art? Too bloody right it is.

Did you need to know all about it in order to appreciate it? No, of course not. If you don’t get a response to it then I haven’t done my job properly as an artist.

But I’d suggest that investing some time into looking deeper at art – stuff that seems a bit obscure perhaps, or that you think is too simplistic to really count – could yield more than you expect.

We don’t have the language that differentiates me and what I did, from your mate who did a really nice picture of your dog. And that’s ok. Both have a place in this world.

But keep what I’ve said in mind next time you’re in a gallery and something catches your eye. Take some time to respond to it. See if you can work out what the artist was trying to say and gauge if you think they’ve been successful. Consider the artist’s personal history and how this is influencing the piece.

And then just enjoy the experience.

About a year ago I was visiting at a friend’s house and noticed they had a book table. It’s literally what it says – a table of any size you happen to have, on which you throw a random assortment of ancient dog-eared friends, shiny new acquisitions, and in our case, books unpacked from deep…

Holy hell, this shower feels good. Pretty sure I’m using up the hot water, but any fucks I could give evaporate into steamy bliss. After ten hours underground proving a new coal hauler design, I’m going to treat myself. And the company I work for is going to pay. There’s a Tennessee barbecue within walking…

What Do We Mean by ‘Pace’ And Why Is It Important? We often hear that books are fast-paced, slow burn or ‘saggy in the middle’. In a nutshell, pace is the speed at which a story unfolds (note that this is not the same as the speed at which a story takes place, e.g. over…

Recently, I came across a fiery argument on multiple social media platforms around the topic a writer compensation. On the face of it, it shouldn’t be a hugely controversial topic – work should be paid for – but as with anything opened to mass criticism you find that many miss the point. Some deliberately. Authors,…

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…” wrote authors’ rights activist Charles Dickens as A Tale of Two Cities began its epic unfolding. He could easily have been writing about the general state of affairs today, particularly the…

Thinking back to January 2021… I was feeling rather stodgy after Christmas excess, and Mrs. Treaclechops had a touch of winter blues, so we decided on a stroll along Wychall Reservoir in south Birmingham. It was a mild 10℃ with a sky of intermittent light cloud and bright sunshine. Not a great variety of wildlife…

Do you remember your first time? Was it exciting? Were you nervous? Did you just want to get it over with? One of the most wonderful of the many wonderful features of the Litopia Colony is The Lab, where writers can go to experiment with their writing in a safe space. Mutual exchange of ideas…

An indie author often lives or dies based on their books’ ratings and reviews. Okay, maybe that was a touch dramatic. Often, it’s a case of succeeding or failing rather than expiring but you get the point. An indie writer’s career is in the hands of the readers they reach and although it is…

Writers are, by definition, people of heightened awareness and sensitivity. If you weren’t, you wouldn’t – couldn’t – be a writer. Yet in a world that increasingly seems to fetishize cruelty, revenge and malice – as attested by our ever-degenerating political discourse – how can the sensitive person protect themselves? The coming period will not…

As the old year comes to a close, I think about things I am grateful for and about fostering good habits for the new year ahead. Which is ridiculous, I know. Why should the day after the thirty-first of December have any more significance for gratitude or self-improvement than, say, March 6th or September 7th? …

My reading of The Complete Works of Shakespeare was almost at an end. The book (only a paperback) had weighed in at 1250g, and the font was tiny, so this really felt like an achievement. It was now so mauled-looking that Will had lost his face and both the bookmarks had broken necks. But, after…

I looked everywhere but I couldn’t find it. It wasn’t in the jumble of decorations packed away from last year. Nor in the Advent calendar hanging by the stairs. It wasn’t in the recipe file with its pink index cards graced by my mother’s slanted script. And it definitely was not hiding in the words…

Well, I’d just read all of Shakespeare’s plays and I was feeling extremely showy-offy. And yes, I’d been totally mind-blown or singularly unimpressed and all the stops inbetween. But I couldn’t say I’d read the Complete Works until I’d ploughed through the poems as well. So off I went. Venus and Adonis Well this…

Cold winds blow through city streets as winter’s grip takes hold and grey souls in downbeat worlds retreat to lies untold. . Rain-lashed pavements now are bare, the forecast speaks of snow, but in grim northern climates an oasis starts to glow. . Christmas days are here once more, those warm enchanting times. Chance to…

Unbelievably, after nearly six months, I had almost come to the end of the complete works of Shakespeare. That lockdown challenge had proved hard to do sometimes, but also impossible to stop. And now I had just two last plays before hurling myself into some lesser known poems and the oft-quoted sonnets. 36. The…

Deep in tribal territory in Jharkhand, India, three schools — one by a road, one in a forest, and one on a hill — hosted eight development education interns from around the world. We were there to learn and teach, but mostly to bridge worlds. Our gracious and welcoming hosts had already treated us to…

My book was looking ragged and my Kirk and Spock bookmarks were bent. But I was determined to push on, despite having never heard of a couple of these. And also unaware that the good, the bad, and the ugly were about to hit me full force. Let’s start with the Ugly, and get that…

Four-year-old Hugh wanted to be a villain. This puzzled my son Jack. If they played Star Wars, it was Luke vs Darth Vader, which made a convenient pairing since neither had to battle against an imaginary adversary. Nevertheless, Jack regularly argued with his friend on the merits of heroism. Hugh, chin set obstinately, refused to…

By now Shakespeare was all Henried out, so he turned to the ancient world to inspire his next set of plays. With varied results, to be honest, but he did get us in the mood with this famous tale of doomed lovers. 30. Anthony and Cleopatra I know Anthony got top billing here, but…

If you read my Christmas Snippets post, you’ll be aware that I suffered a psychotic episode in 2019. This was followed by a long period of anxiety and depression. In 2020, my mind couldn’t take any more. It shut down, and I left my family home. My boys were just four and seven. Things came…

This part of the book had the men taking centre stage. Shakespeare had hit his stride. At least, that’s what I’d heard, and I was interested to see if they lived up to the hype. Were they really mad, bad, and dangerous to know? Well, let’s see. 27. Othello After finishing this play I picked…

In August, he smiled at the memories of 65 Decembers, and put away his razor. . The ruddy complexion, jovial disposition, and expanded waistline where already his by right of genes, a penchant for English ale and a passion for bulked-up curries. . Throughout September, October, November and into December the beard became luxurious with…

My paperback version of The Complete Works of Shakespeare was starting to look properly shabby. I’d bent the cover back a lot, and sat cups of tea on it a few too many times. It now looked like a book that got READ, which made me feel I’d was adulting like a boss. With that…

Port and Lemon and Dirty Jokes My nan was the type of woman who couldn’t walk to the shop without stopping at least three times along the way to chat to someone she knew. She used to play a card game called Stop the Bus with me for a penny a hand. She kept budgies…

I was approaching the halfway mark of my Shakespeare-a-thon, and methought it was time for some top scores. The Big H was coming up, so I was well excited. That’s got to deliver the goods, I thought, otherwise why was it quoted so often? But first, there was this. 21. As You Like It…

Over the years, I slung my guitar in many bands, and although not exactly an international rock star, I have had the good fortune to play on a few minor tours in and around various European countries. Back in the mid-nineties just such an opportunity arose. A ten-date jaunt around Belgium and Holland. We completed…

Much Ado About Nothing left me in a good place, so the thought of another comedy coming up was quite welcome. But would it deliver the goods? 19. The Merry Wives of Windsor If I could change the title it would be this: Falstaff, part III, Die Hard with a vengeance. Poor Falstaff…

At first encounter, she slapped me on my backside and declared, “I don’t recognise that bottom!” . Then she skipped away on one of her missions to share a cuppa and a slice of humanity with a lonely soul. . At her behest, I carried bags of…

I don’t want to bring you down, but Christmas isn’t always fun for me. It’s a difficult time for a lot of people. The pressure is on to have a good time, but it’s not easy. The ideal of family around the table in a beautifully decorated, warm home, surrounded by love and gifts is…

It is 1975. I am a teenager, listening for the first time to a protest song by Greg Lake. The tune mesmerises me, the riff stiffens the hairs on the nape of my neck. I want to hear it over and over, but I don’t get pocket money: I just have to hope they play…

When I was eight years old, I auditioned for a part in my school’s Christmas play, Christmas is Cancelled! Despite being a shy child, I loved singing and role-playing and my timidity was overridden by the thought of getting to experience my dream of performing on stage. The audition took place in the school hall…

I was cracking on with my stupidly self-imposed lockdown challenge to read The Complete Works of Shakespeare. I’d met a few Henry’s now, and although I knew one of them was meant to be rousing stuff, I had no clue which one it was. Could it be this one, I thought? 16. Henry IV part…

Over the river and through the woods To Grandmother’s house we go. The horse knows the way to carry the sleigh Through the wide and drifted snow. I am retired and live in Hawaii after teaching and administering for the school district in Los Angeles for many years, but I grew up in Western New…

I’d now hit the stage where I was half enjoying this challenge and half wishing I hadn’t told everyone I was gonna do it. There were expectations, and I’m never good with those. But I knew many of the famous plays were on their way, so that was good. 14. The Merchant of Venice Sadly,…

“The werewolf’s bride is late.” The words echoing in my head were spoken by a black horse. With a toss of its mane, the horse became a giant bird with wings like grey shrouds. The thing’s eyes remained yellow. As drunkard’s piss, granddad would say. A woman held up an admonishing finger, her face hidden…

I’d now encountered a few stand-out plays, in my great Shakespeare-reading marathon, so I felt quite buoyed up at the prospect of what was approaching. But then I was hit with this one. 11. King John I’m not saying this was mind-numbingly boring, but I had insomnia that night, and reading this was the only…

Lady Brimstone-Smedley bought two female parrots, Polly and Dolly, but was shocked to discover they kept shouting out rude and inappropriate remarks. She sought advice from her parish priest about curing them of this embarrassing habit. The priest was mortified at the things the parrots were shouting. Polly squawked, “Do you fancy some hanky-panky?” Dolly…

In my quest to read all of Shakespeare from start to finish, I finally made it to plays that I’d heard about and seen on the telly. I rubbed my hands in glee at what awaited me. Cover your eyes, I told Spock, it’s gonna be randy youngsters going all extra. 9. Romeo and Juliet…

Don’t expect people who barely know you or don’t know you at all will promote your book. It’s not likely that people will go out of their way so you can climb a step up the ladder to success, unless they are invested. Nor can you count on the many faceless friends, acquaintances or followers…

As you’ll know if you drop by the Colony between the 7th of each month and the 21st, we run a monthly contest between those dates in which you’re challenged to write One Perfect Sentence… It might be the first sentence to a book, the very last sentence – or something else entirely. It’s fabulously…

Ten minutes before I left the house, my boss called. “The science class is cancelled today. Take Jisoo and Jennie instead. They need adjective practice.” (By the way, this happens a lot. I once opened the classroom door to find six quiet ESL teenagers instead of the rambunctious kindergartners for which I had the mood…

Full of enthusiasm for my lockdown project of reading The Complete Works of Shakespeare, I wandered blindly on to play number 5. Some time later I stumbled back out, wondering if there’s any wriggle-room on those do not drink bottle warnings, as I felt the need for some kind of absolute cleansing. Should I sit…

The Long and Short of It I enjoy writing short stories, which is a complete one-eighty compared to how I used to feel. I used to wonder how an author could convey so much meaning in so few words. It took practice and the motivation of entering competitions to change my mind. Love, Christmas is…

When I first started down this self-publishing journey, I heard quiet rumours of the dangers of scammers. I knew they were out there. I knew they wanted my money (What little of it I have), and I knew they had no shame. What I didn’t know, and was unprepared for, was just how many of…

We all remember those drawn out days of the first Covid lockdown, right? I don’t know how you coped, but while other people were learning new languages and putting out their trash dressed as Ru Paul, I decided to do something quite useless. I would read the Complete Works of Shakespeare. Oh yes. Armed with…

Thank you for bearing with me. As a reward, we’re leaving high school. We’ll only revisit it in my dreams from now on. I promise. Okay, we’re going to fast-forward now. I won’t bother you with the interim. I think we should let it be said that I learned a lot that day. You’ve just…

I am glad you’re still here. Come, sit down with me. We’re in my English class. Spring 1994 is the pre-Axe-Body Spray era, if you’re wondering why you’re not identifying it. I like English class, in general. When I was 14, I was awarded a prize for a short story, and Mrs. Williams has read…

This is a story of grace, not of sadness. I’m saying that because it won’t feel like that. Not initially. I’m just going to take you on a journey with me, but only if you’re ready. We’re going to the fall of 1993. Take my hand. Watch your step. We’re going back to my high…

The Good There’s so much to love about writing – the excitement of that initial spark of an idea; the stimulation of the challenge to make it work; that feeling you get when you find the perfect word/phrase/sentence/paragraph to express exactly what you mean in the most eloquent way you can; the thrill of positive…

I’ve discovered a number of things to do with cloth serviettes which in today’s age we seldom use. Personally, I don’t use them anymore because I tend to look upon them with suspicion; as being unhygienic, just like cloth handkerchiefs. One gets a sense of nausea, a feeling of disdain in having to re-use something already…

I recently participated in ALLi’s SelfPubCon, which focused on the business side of writing. There were sessions on using social media, monetising YouTube, website design, using AI for marketing … I watched video after video that made my brain turn off. Video after video teaching me how to cash in on the advertising deluge we…

Bert and Harry had met at the ‘Hunter’s Moon’ village pub every Wednesday night at 7 pm for the last 15 years. Both now suffered from ‘old man’s bladder’, and restricted themselves to two pints each. Harry, being the more progressive, would choose lasagne or a pasta dish for his meal, whereas Bert…

Giving Feedback The title of this post is a sentence that’s often used at the end of a fellow writer’s feedback in the Lab, and I think it’s perfect. The first time I submitted work for critique and someone responded with this line, I felt a huge wave of relief. It says so much in…

I have to make a new word. This is not uncommon for me. Legiterally is now, officially, a thing. Coffeed is a passive verb that has long need to be in existence. I am still looking for one for accidentally on purpose and those people who talk on speakerphones in public if anybody’s feeling frisky.…

There has long been an association between mental illness and creativity with seemingly endless examples of successful creatives affected by anxiety, depression, bipolar and other mental disorders: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Edgar Allen Poe, Virginia Woolf, Leo Tolstoy, Sylvia Plath, Ernest Hemmingway, J.K. Rowling, Stephen King, Stephen Fry, Emily Dickinson, Franz Kafka, Matt Haig, Van Gogh,…

We are back from a river cruise down the Danube from Budapest to Bucharest. Well, what did we see? We were amazed at the people who are beathing; that is, the air of freedom. New entrepreneurial enterprises have opened up—many businesses started by people under forty. In fact, our program director on our Viking cruise…

When, after the August sun, the first rains fall there’s something nostalgically magical that lures you outside or look through a window in silence and be embedded with the atmosphere. You feel the moments of childhood crowding around you: when the first days of school were mingled with the anticipation of falling leaves; when learning and the…

It was an irresistible afternoon, the gorgeously seductive late summer / early-autumn sunlight inviting me to come play in the woods… how could I refuse? So I grabbed some wild garlic bulbs and a trowel and hied me to the dappled paradise. Work could wait, at least for a couple of hours. Bulb planting is…

I’ve been avoiding the subject of AI for a long time. I’ve tried to ignore it, tried to pretend it won’t be as big a deal as people are making out, and that it will find its place somewhere and make life a little less cumbersome. But the more time that passes and the more…

I’m Fine Whenever I meet someone new, I try to learn their language. I don’t mean French or German; I mean things like what they convey without actually saying the words, or the way they might say something but mean something different. For the latter, take “I’m fine” as an example. It can mean different…

Come over here for a moment, would you? But be careful of the edge of the table, it’s rather sharp. Good. Now you can see things from my side of the desk. That towering pile you see in front of you? It’s what some unkind publishing folk call “the slush pile”. Yes, most of it’s…

Thinking back to December 1973… a village called Oberjoch (over the hill) in the Bavarian Alps. Six feet of snow! I was learning to ski with a six-man unit from 49 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. It was a 2-week course, and we manage to ski fairly well down the smaller slopes…

I recently had a great movie night with my daughter. We made a fort (three kitchen chairs with a blanket thrown over the top and far too many stuffed toys to get comfortable), we made popcorn and a bowl of Skittles, and settled down in the living room to watch a movie with all the…

Well, it sort of is… I’ve been fascinated by dystopian fiction for many years – any story which explores a dramatic change in the way of life for a society, if not humanity (which can of course cross into the post-apocalyptic sub-genre). But it’s not just the ‘big picture’ of these novels which intrigues me,…

Marcel Duchamp said this: it’s art if I say so. He’s the guy who stuck a urinal on the wall and called it ‘Fountain’. And ever since he did that, the art world swivelled on its axis and became a place where apparently anything goes. And usually for a gazillion quid. Which really gets the…

As a writer, I tend to focus on plot. I love a good action scene, and I also enjoy writing dialogue (probably stems from loving to talk, myself. LOL!). Over the years, I’ve developed a method for outlining my novels that’s sort of a mash-up of different methods I’ve read about. I start with a…

The 28 Delegates from Earlston in Scotland here on their annual twinning visit with Cappella Maggiore attended Mass at a local church in Anzano. Fr Mario wanted to say a few words of welcome to them in English and then would I translate simultaneously the rest of the sermon. I didn’t say no, I just…

As a kid, I watched Star Trek. Some things have come true. I remember at the market you had to push to open the door. On Star Trek, the doors opened automatically with a SWOOSH when Captain Kirk made his dramatic entrance (wow, he’s still with us as I write this). A few years later…

Out of the Mouths of Babes This post was inspired by a comment made by my eleven-year-old son. It was prompted by his question regarding what I’d hypothetically create a YouTube channel about (reading and writing novels of course!). He summed up in one sentence what I took years to work out: “The most important…

The sun blazing down on this our fragile humanity enticing us to the cooling waters of the sea or the breezy shade of mountain trees. It is time for ball games on beaches, hide and seek on mountain slopes: laughter, friendship, care-freeness. It is time for distraction, the distraction that once saturated must eventually lead…

There are debates about audio books vs paperback vs digital formats. This post is not about that. Although that would be an interesting post. But I will not try to convince you to listen to a book if that’s not your jam. Well, I won’t deliberately try. As for SFF… you either love it or…

I recently wrote a blog post about bad writing in current media and decided that this month I would write about good writing instead. Bad writing is low-hanging fruit; it’s easy to spot, and easier still to complain about after you realise something has relieved itself on it. The Acolyte, the show I talked about…

My neighbouring village in Northern Italy enacted the 1917- 18 Year. They called the event the “L’an de la Fan” which is a Veneto Region dialect expression for “The Year of Hunger.” There was something special about this year. Apart from the massacre that left a painful dent in Italian history, it also attracted the…

Be Brave I’ve been writing seriously for years. The more I wrote (and read the work of other authors), the more I experimented with different genres, voice, style and structures. I realised I had nothing to lose by going down experimental rabbit holes, except time and effort. But hey, writing is a craft, right? And…

My Writing Journey During my formative years, I had spells when I thought I’d like to be an author when I grew up (if we ever really do). But I didn’t know any writers and it seemed like something that other, cleverer, more privileged people did, not someone like me. But when I reached my…

Donald Sutherland is gone. I saw him on stage at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles years ago in a play. What can one say? M*A*S*H etc… I knew Eddie Albert and bid him adieu nineteen years ago. Wow, stop the clock! I sat next to him at a few dinner parties at our…

I’ve never liked my voice. I’m not alone. People, in general, hate their voices. We are simply not biologically intended to hear our voices the way that other people do. I hear it and I think, “Who’s that guy?” No, actually, I don’t. I don’t do that. I hear it and I think, “Who’s that…

This year, for the first, time, I noticed the absence of something in June: rainbows. I’d never been particularly in love with them. The fact that Subaru will slap a rainbow on their ads, or that once a year a random company I never really patronize will reassure me how much they like the gays,…

Lately, I’ve been hearing lots of complaints about awful writing. Not mine – people aren’t saying it to my face anyway – but some movies and television shows that are getting some scathing reviews. Some cry that this is racism, homophobia, sexism etc. That these criticisms don’t hold water because of the place from which…

Originating from an informal meeting of finance ministers in 1973, in Washington DC, two years later the G6 established at its first meeting in Château de Rambouillet the following principles: a united commitment to promoting free trade, multilateralism, cooperation with the developing world, and rapprochement with the Eastern Bloc. In 2024 the group, now G7,…

A long-lost friend dropped by recently. Myka was in Berlin for a conference, and found herself with a free evening. We offered her a barbecue, a bed and a walk in the woods. Myka was thrilled. Like us, she had bought a house on the edge of a wood. She loves forest-bathing, or walking away…

Be Up-Front Agent Pete often says that writers should play to their strength and put it front and centre in the opening of their novel. It sounds so obvious but this hadn’t occurred to me before I heard him say it. Are you good at dialogue? Open with a conversation. Do you excel at action?…

A Rose By Any Other Name Would Smell as Sweet, Right? The Silence of the Lambs, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Elinor Oliphant is Completely Fine, 1984, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, The Colour Purple – titles that we remember, titles that I love. But what makes them so effective? And do titles affect…

Food, travel, books, movies, television shows, and on…and on… A family member of mine doesn’t like avocado. Won’t dip his chip into guacamole. YUM. A friend I dine with loves escargot. YUK! Slimmy crawl ya’all. I recently watched—what I thought would be—a simple detective series, but when in episode 7 it was revealed the detective…

I always find Beta reading such a great opportunity to learn. I discover things that I’m sure I do myself as a writer that I critique as a reader. In my last few rounds of beta reading, I found myself thinking about the gap between being “the writer” and being “the reader.” I mean, of…

My experience with deal sites. This one is for the writers. Last week, I ran a promotion for my novel The Trouble with Prophecies. I slashed the price down to 0.99 for the week in an attempt to get sales going. For context, the last time I ran a promotion I made the book free…

I’ve always had a sense of affinity with the Mystic Padre Pio and the fact that he was born the same day I was, May 25th, makes that bond even closer. For years he drew upon himself the abuse of many, including that of the Pope because people were sceptical – claiming to have the…

Don’t Start with a Character Waking Up, Looking in the Mirror, or with a Hangover On Pop-Up Submissions, we received a lot of openings like this. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, at least in my humble opinion. It may be a cliché, but Fifty Shades of Grey starts with Anastasia Steele looking in the…

(Disclaimer: although not politically perfect, I’m going to use the familiarity of the term ‘disability’ rather than, say, ‘differently abled’ in this post.) I’m gonna say, straight up, that I can’t tell you how to write about disability, primarily because everyone’s experience is different. But I might be able to give you some food for…

I decided to self-publish my contemporary romances after unsuccessful attempts at the traditional route. There are pros and cons to making this decision and lots of issues to consider. Will you pay someone to edit and format your novel? What about the cover design? What platform/s should you upload to? How will you market the…

The pebble skimmed the surface ten times before running out of momentum, then seeming to flounder for a split second, sank into the dark still lake sending ripples radiating outwards. “Ten, dad. Beat that,” said Michael. “Hah, easy,” I said. I scanned the shoreline and spotted a perfect skimmer. A small piece of ancient flint;…

“I’m home, darling! Early finish today. Hurrah!” The masculine voice echoed through the house, and fell on the ears of Mrs Brown and the insurance salesman. “Quick!” she exclaimed. “It’s my husband. He’ll go crazy if he catches you.” “Who…what?” the salesman stuttered. “I didn’t expect him home yet. He’ll commit murder if he finds…

The 25th April is a national holiday here in Italy and it’s called Liberation Day. I had noticed, however, as the years went by, the enthusiasm to celebrate was dwindling a bit and basically I put the cause down to the fact that there seemed to be some confusion among the various sectors of Italian…

“So, what is the worst thing about being a writer?” my neighbor asks me at the Spring Social. “Ummmm,” I say, looking past him to the office. I had forgotten that there was a Spring Social going on today. I see the notices clipped next to my door for them a few times a year:…

Remember lockdown? Remember how we all got a bit excited in the first one and felt we had to make it count? And some of us, you know, wrote a book? Yeah. Turns out quite a lot of us were wrong there. 80,000 words of relatively competent sentences don’t always add up to a book.…

Rules and Commonalities I’m not a musician but even I know that songs have a structure, verses and a chorus, that they often have a beginning, middle and end, that they can build to a crescendo, explore a narrative, evoke deep emotion and stay in our hearts forever. But just what is the magic ingredient…

I’ve been doing the daily Wordle puzzle since it started. In case you missed it, Wordle is an online game that gives you six chances to guess a five-letter word. It was invented by Josh Wardle, a software developer, for his girlfriend who loved word games. Just for fun, so the story goes. Until he…

Last time, I spoke about stories that stay with you – or more accurately, the ones that don’t. This month, I want to take some time to unpick what makes a good story. One that lives in your psyche days, even years, after the final page has been turned. I think it’s fair to say…

You Are Not Alone Most people experience rejection when querying. Beatrix Potter, author of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, got so many rejections she ended up self-publishing. Now, over 45 million copies have been sold world-wide. Rudyard Kipling was told that he didn’t know how to use the English language. F. Scott Fitzgerald was told…

Time and Head Space When I was teaching full-time, I found it difficult to fit in any writing. It’s definitely not a nine-to-three job! My evenings and weekends were taken up by planning, preparing and assessing, as well as various administrative tasks. Not to mention the demands of family and general life. However, switching to…

“He’s gonna stuff me.” “Don’t talk like that!” Collo grabbed my arms. “He’s just a twinkling fairy!” “Yeah, but look at the size of him!” “Don’t think like that! You can beat him… you’re representing ‘B’ troop. Remember your training! Don’t let him catch you… keep moving… you’re faster than he is.” “Yeah, but he…

In that heady, comforting, all-encompassing safety-net that is the deep love forged by a long life together, my soul-mate and I tried to find ‘our song’. Amongst all the haunting melodies and time-tested lyrics, surely we could find a single song that expressed the depths of our feelings for each other? He suggested some, I…

Who the hell do you think you are? I once heard that authors alternate between two perceptions of their work-in-progress. One is: ‘This is amazing! I’m a bloody genius!’ The other is: ‘This is the worst thing ever written! Ever! In the whole history of story!’ The truth, of course, is that it’s usually somewhere…

The International Children Books Illustration Exhibition opens its doors for six weeks every year at Sarmede, my home town, gathering the usual crowd of fans and supporters from various parts of the country. The Exhibition used to be held in the Town Hall of the village which has permanent mural illustrations done by the artists…

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,” grumbled Jo, lying on the rug. That opening line is indelibly inked in my memory. Other fictional characters captured my childhood imagination before the March sisters: Anne of Green Gables, Black Beauty, Big Red. All great stories for children. But ‘Little Women’, Louisa May Alcott’s coming-of-age story set…

The Brother has a view on modern verbiage ++ Now, c’mere ’til I tell you this. I’m all ears. What is it? The brother has barred himself from watching television above in the digs. Excuse me? Barred himself for the foreseeable future on account of him having been roaring at the TV in the residents’…

We All Have Our Own Opinions Of course we do! Life would be very boring if we didn’t. But there are elements to story that seem to be essential and universal. I’ve listed some below but it’s not exhaustive and I’m interested to hear other ideas. Character I often hear authors talk about the…

Say What? Writing a novel with more than one point-of-view can be tricky. How can you juggle different personalities and motivations – and somehow use them to tell a balanced, coherent and compelling story? How can you ensure that each character has their own ‘voice’ (something that I find extremely difficult to achieve!)? But does…

There’s something about cats. Yes, in January I burst my eardrum trying to cure the ear mite infection I caught from our two. They wont be sleeping on the bed pillows after that. But I mean more. The truth encapsulated in this post from Jennifer Adcock, writer. “You know who doesn’t get impostor…

Sorry! I’ve been a tad disingenuous with this title because I’m not referring to the act of writing on behalf of others, but rather the literal act of writing about ghosts! Trick, or treat? Of course, there are many ghost stories, especially in the horror genre, but I’ve selected a few from other genres to…

The last few weeks, I have been replaying a video game from my distant past. An old favourite by the name of Final Fantasy VII. I used to play this game almost once a year; I kept going back to it again and again throughout my childhood and often used to inform my imaginative play…

“Do you still see the Bulgarian?” The question tumbled out. “Yes.” Her reply was instant, instinctive, intuitive. “His name is Krasimir.” “Sorry.” He stuttered his response. “I didn’t mean to pry… just a silly question. None of my business. Sorry.” “It’s OK.” She attempted to heal. “I have no problem with your question. It’s not…

Over achievers rarely herald from untroubled upbringings. Being born to a mother with low confidence in her own abilities wouldn’t have been so bad, had she managed an ounce of confidence in her own children. Such is life. The poor woman was bullied by her father. He, in turn, had been emotionally wrecked by the…

Ciao. Getting ready for our two-week trip to Northern Italy. Northern Italy you say. What about the rest of Italy? Well, in due course. A friend of mine recently went to Italy and did the typical, American 9 day, 10 night tour of Italy on a bus. “Bring down your luggage and be on the…

“Aren’t you supposed to be writing?” I shove the nagging question away. The computer will still be there when I return to it, cursor blinking patiently at the top of a blank page. It is Thursday, one of my two weekdays designated for writing. I am cradling a cup of coffee and standing in the…

An Issue of Trust I’ll admit, novels with an unreliable narrator are not everyone’s cup of tea, but I love them. You start off thinking the character is taking us on a believable journey and that we can trust their telling of the events, then unease creeps in. We start asking questions. We wonder where…

Mention the word Trope to us writers and we’ll recoil. Add the word Cliche and you’ll see us running for the hills. These two five-letter words are not what any of us want in our wonderful, new, original, works, right? But consider this: things only become tropes when they are overused, and they only become…

My three psychological novels have unlikeable point-of-view characters. Without balance, they can appear two-dimensional – and I’ve discovered that achieving that balance is rather tricky! What do I mean by balance? I suppose I’m talking in terms of the reader’s perception. Is the character’s dark side countered by a bit of light, or a reason…

I am made of regret, but not of sadness. During my brief and somewhat misguided youth, I spent my money and spoke my mind. I moved countries and continents. I learned languages, had adventures, and spent my life coloring outside the lines. I don’t recommend it unless you want to come back to where you…

A writer friend of mine and I have exchanged writerly encouragement to each other for many years. The most frequent reminder we bounce back and forth is that writing is really hard. We take baffling things in our life, in society, in the world, often stuff that strike us as chaotic, and we try to…

Dear Grandpoppypops Wish you were here? Look at the size of the stamps now! So much larger than the penny black you showed me from your visit. Not much has changed so far as I can see in human structure, society is still set on exploiting other sections of itself. Your industrial revolution really set…

Flann O’Brien’s much-loved character – The Brother – transported to the 21st century. What would he make of contemporary trends and fads? This episode imagines his reaction to Molecular Gastronomy, Nouvelle Cuisine, and the tampering of a subject very close to his heart. ****************** Now the brother has a thing or two to say on…

This is my first post on this forum, so I wanted to do something short and light. What types of distractions interrupt you when you’re hammering away at your keyboard? The phone rings? Your significant other shouts at you from the other side of the house? Your cat comes in and plops down onto your…

Go beyond the usual guide book notes of the Trevi Fountain and savour its unexpected pleasures.

PART ONE Walk through the heart of Rome and you will be lured in one direction and then another as instantaneously as a magnet does with a piece of iron… The Pantheon will attract you with its metaphysical force of the gods, the Foro Imperiale with its magnitude of power… while the Fountain of Trevi…

My first day as a professional writer, I lifted a police report from the pile at the Coffeyville station and read “Murder.” Now, this was a small town, and I was pretty sure this sort of thing was a rarity. I wasn’t sure there had been much in the way of this most heinous of…

First Things First I’ve never understood people who have a favourite song, book or film. Surely your choice depends on your mood. It’s the same with genre. Maybe today I fancy reading something light-hearted and fun. Tomorrow I might want to feel a shiver run down my spine. The next day I might be enticed…

Lucky seven they say, but the morning I had to load that many strong-minded mustangs onto a lorry at the top of the Swiss Alps with a 4am deadline, it seemed a doomed number. Especially when lorry drivers with ferry schedules and EU regulations have famously short fuses. They have been known to back out…

Hands up anyone who’s had a bit of writer’s block? Looking around I can see that’s pretty much all of us, right? Even you at the back, hiding behind your laptop screen, pretending you’re doing research into character types, whilst actually playing Royal Match and posting videos of your cat. Why do we have such…

I’m delighted to give you an early peek into this year’s Litopia Book Club selections, together with relevant purchase links. It’s a particularly strong and carefully-selected list, and as you’ll know if you’ve attended one of Jason’s riotous Zoom sessions, a good time can be guaranteed for all! For further information and exact dates, please…

Selling highly-priced, poor-value seminars and writing courses to aspiring authors isn’t just unethical – it’s also damaging to the publishing industry, says Litopia’s Peter Cox in this article for “The Bookseller” That old scoundrel Sam Brannan would have felt completely at home in today’s publishing business. Sam, you may recall, was the original promoter of…

Get The Digest

Subscribe to our occasional email featuring all the best writing from the Colony.

Free to subscribe, unsubscribe whenever you want (but we don't think you'll want to!)