Self-esteem and stuff I’ve learned about it

Nearly forty years ago I was taken to a self-development workshop by a new boyfriend (and yes, I did think maybe he was inviting me to join a cult, but he was hella cute, so I went along anyway). And for the next ten years I became immersed in the process of discovering how my brain played tricks on me and what I could do about it. Resulting in me teaching self-esteem courses, and generally having a better life.

And now I’m a writer in a wonderful community of writers, and I see how often the amazing people around me doubt themselves, or underestimate their talent, or struggle with ‘criticism’, and I feel for them. So, for you guys, and for anybody else for whom this is any kind of an issue, here’s a distillation of stuff I’ve leaned over those forty years. Hope it makes you stop, and pause, and think about being kinder to yourself.

Belief systems and how we create them.

When we are born, we use a part of our brain that has remained unchanged since we were cavemen. It is where our basic survival instincts are managed and is often referred to as the Primal or Hind brain. As cavemen, we just need to stay alive so we can continue our species. So, food, water, warmth, shelter, safety, awareness of danger – these are the things that matter. And getting these needs met is pivotal.

Once a child has got the hang of feeding itself, mobility, and basic language, the primal brain’s next concern is keeping the body alive to grow to reproductive age. It must now also learn the rules of what is safe and what is dangerous. So, along with all the physical basics, the Primal brain becomes alert to clues about what is harmful/painful and what is safe/pleasurable.

It does this many by applying these criteria – am I safe, loved and valued? These may seem more advanced than you’d expect, but to a caveman brain, a baby that has value is more likely to grow to adulthood and less likely to be abandoned.

How it works is like this: any time the child is in a situation that one or more of those criteria is thin on the ground, the primal brain will immediately assess the situation and make judgements calls to protect the child in the future. Is this a situation that must be avoided? Is there a lesson here that should be learnt?

The goal of the primal brain is to stop that event occurring again, or to make navigating it as easy as possible. It all sounds like a good system, right?

But wait. Three things crop up here that are worth noticing.

1) The brain hates helplessness.

Helplessness equates to being the victim in the situation, and therefore the caveman baby will be more likely to die.

The brain wants to find a solution that gives agency to the child. That way is safer: thousands of years of evolution have proved it to be so.

But because it isn’t the reasoning frontal cortex, it’s thought processes aren’t always rational. It can’t, for instance, accurately assess a situation like this; ‘mummy and daddy are arguing because money is short, and the car just broke again.’ It just doesn’t have that capacity.

No. The primal brain joins the dots like this: if this situation is my fault, then I can change my behaviour and fix it. If I have agency in the cause, I can prevent reoccurrence. So, it will conclude something like ‘mummy and daddy are scary, and I’m frightened, and if I was less stupid/clumsy/bad they would stop shouting and love me again.’

This is genuinely the best it can manage.

Consequently, bit by bit, the primal brain invents ‘rules of behaviour’, which get embedded and usually follow this pattern: this happened because I am too XYZ, so I must now behave differently, ensuring I am safe/loved/valued again.

2) The Negative bias.

If things are going fine, the primal brain can step down and not worry. It is negative experiences that are more likely to threaten the safety of the child. Ergo, the primal brain is hard-wired to actively look for and focus on negative experiences. Negative experiences ‘stick’.

3) These rules are created in the primal brain, which is also sometimes known as the Instinctive brain.

These basic ‘survival’ tools are considered absolutely paramount and not to be messed with. Survival depends on NOT standing around making thoughtful and considered decisions when the sabre-toothed tiger is about to pounce. So, our reactions to trigger situations will follow these rules instantly, without running things by our reasoning frontal lobes first. Most of the time we won’t even know it’s happened until after the event.

To recap…

Any childhood experience that held any sense of threat or pain or sadness helped create a rulebook of how the child (then teen, then adult) must behave so that it could ‘survive’ successfully. Be less this, more that. Do this more often, don’t behave like that. This is good, that is bad.

And because the primal brain didn’t need to focus on the good stuff so much, many of those rules were about perceived ‘negative’ traits and things that were ‘at fault’ with the person. That was the way it was programmed, to ensure the child’s safety.

Plus, to really make that rulebook effective, when any situation activated a belief, the reaction would be instant and without fore-warning.

In today’s more advanced and sophisticated society, this creates adults with accusatory belief systems that focus more on the negative, and which are not always helpful or wanted. In fact, they are often debilitating, stunting and unsupportive. We almost never measure up to the rulebook our primal brains have written for us.

But remember…

However full of these thoughts we are, it is never our fault for having them. It is not a character failing. It is not a weakness. They are part of an evolutionary process that is millennia old.

There is not a single person on this planet who doesn’t have this kind of roadmap to some extent. It is impossible to survive childhood (unless you’re born a sociopath or psychopath) without your primal brain building a rulebook of this sort.

It did its job. It kept you alive. It doesn’t know that society is very, very different now and the rules to navigate it are no longer the same as in caveman days.

What can we do about it?

It’s all very well knowing that we have that inner voice in our heads, and understanding how it got there and what its purpose is, but what do we do about it? Well, as adults, we can use our frontal brains to help mitigate and disassemble these thoughts, freeing ourselves from unwanted and unhelpful behaviour patterns.

The first thing to focus on is spotting that it’s happening. Sometimes it is quite obvious – that ‘voice’ can shout quite loud – but often it is more insidious.

So, what then? The clue is in your feelings. Any feeling that is less than happy or comfortable is a sign that one of your beliefs is operating.

Now, it’s important to notice the difference here between feelings and thoughts.

A feeling is a physical sensation or an emotion (and note that numbness or a sense of not feeling anything, is also part of this).

Everything accompanying that feeling is a thought.

These thoughts will include all that negative chat that pulls down our sense of self-worth.

And it’s worth noting that sometimes the thoughts will disguise themselves: sentences that begin “I feel that you…” or “I feel as if I’m…” are usually thoughts.

It helps to write them down so you can take a good look at them. Preferably when you are right in the moment.

Because the next thing is to get your frontal lobes to start doing some adult evaluation of the story these thoughts are weaving.

This is the time to verify if what the beliefs are telling you is valid.

Here’s an example.

Does your oh so helpful brain tell you you SHOULD have done something else?

This is a very common clue word that a belief is running. Everyone has ‘shoulds’.

But ask yourself if your ‘should’ thought is really true.

If, for example, it says you should have known something. Well, let’s verify that.

If this was knowledge that you knew very, very well, were there other stress factors at play that might have made you misjudge the situation?

Or was it something you just figured out because of this incident, in which case how could you have known beforehand? Did the other people involved give you all the clues necessary to know this in advance? Or was it just a culmination of things that led to you making a mistake?

The ’belief’ isn’t equivocal or measured – it is certain you SHOULD have known. But, thinking about this with more perspective, is it really an inalienable truth? Or just something that, with hindsight, you wished you’d thought to do?

And this verification is important, vitally so.

Because when we believe we absolutely should have acted differently, then we include add-ons. And these add-ons come from that protective-brain desire to have agency in the situation, by claiming the problem as our fault. And it will run something like this: because I should have known better, then it must mean I’m stupid, or selfish, or lazy, and people are better off when I’m not there, etc.

And these are the kinds of thoughts that bring our hearts and souls total misery.

But when we verify things, we gain perspective.

The truth of the situation may turn out to be this: I didn’t realise this would cause such difficulty as I was doing the best I knew how. But now I understand more, and I’ll know better for next time.

OR, actually, there’s no way I could have known that this would escalate. And although I wish I’d done it differently, I couldn’t have predicted how things would go.

Verified thoughts.

THESE thoughts are much kinder. They allow for us to make mistakes, to learn as we go, to accept our humanity.

They don’t attack our sense of self-worth the way the unverified beliefs do. They acknowledge the complexity of a situation, and invoke our wisdom and experience.

Beliefs are rulebooks, remember. Designed to try and keep us from experiencing ‘dangerous’ (ie. upsetting or difficult) emotions. The beliefs want us always to be ‘safe’.

And so they will be full of things that start with words like this: –

I must be…

I should never…

I should always…

I can’t…

No one will love me if I…

Life will be hard if I …

People will think I’m…

It’s not okay to…

These lists of things we must measure up to can be endless. And exhausting. And the crucial thing to remember about them is they were created when we were tiny, by our un-reasoning brain. The chances of them either being correct or relevant now is infinitesimal.

And so, using our common sense can be the start of the dismantling process. And the start of us treating ourselves with forgiveness and empathy.

But there are pitfalls.

The brain thinks the beliefs are cast in stone, and will try to adhere to them like Moses on a mountain.

Your brain will ‘tweak’ what you think it told you so that it sounds entirely reasonable: –

“Yes, but being kind and thoughtful to others is a good thing. I don’t want to be selfish and thoughtless.”

This is a trick.

If you write down exactly what you’re thinking when that belief has been activated and you are right in the thick of it, you’ll notice it’s actually saying something more like this: –

“You MUST be kind and thoughtful to others, AT ALL TIMES, or everyone will see just how thoughtless and selfish you really are.”

As you can see, that is not quite the same thing.

Being kind and thoughtful is great. But is it appropriate in every situation? No. And the accusation that you are not worth anything UNLESS you are kind and thoughtful is just cruel. No one deserves to be told that.

In summary.

The thing about a belief system is this – although it is doing a massively important job in getting us from birth to adulthood, it is also cloaking our sense of self-esteem.

As a new-born baby, our sense of self-worth is through the roof (as it should be). We KNOW we are the most important person on that planet, and we will scream for our needs to be met without thought or consideration for others. We wouldn’t survive as a species if we didn’t.

But, as we get older, that screaming becomes less welcome to others, and bit by bit, we start internalising the social rules we now have to live by.

By the time we are in school we already have a list of should and musts and must-nots as long as our arms.

And each of them carries the additional weight of thinking we’re of less value if we don’t follow those rules.

Even with the most conscious and loving parents in the world, there are other influences in the world where we will pick up these ‘rules’.

And slowly, our sense of self-worth gets covered.

So, by dealing with our belief systems, and choosing which to adhere to (yes, fire burns, sharp stuff cuts, all that is good advice) and which to discard (no, I’m not obliged to be the only person on the planet who never makes a mistake) we can start uncovering our sense of self-worth once again.

We don’t have to build it – we just need to remove the stuff that is stopping us seeing it and accessing it.

So, that is the gist of why it’s good to use verification as part of the process of dealing with unhelpful beliefs.

I think positive affirmations are great, but they won’t make much of a dent if the opposing beliefs are allowed to run unchecked.

But used as part of a truth-telling process, after you’ve uncovered the lies you tell yourself, they can help your compass point true North again.

And for us writers, it can help us separate criticism of our work with criticism of ourselves. It has helped me develop a rhino-thick skin in the face of criticism, feedback and rejection – all of which are part of the job. I hope it helps you too. xxx

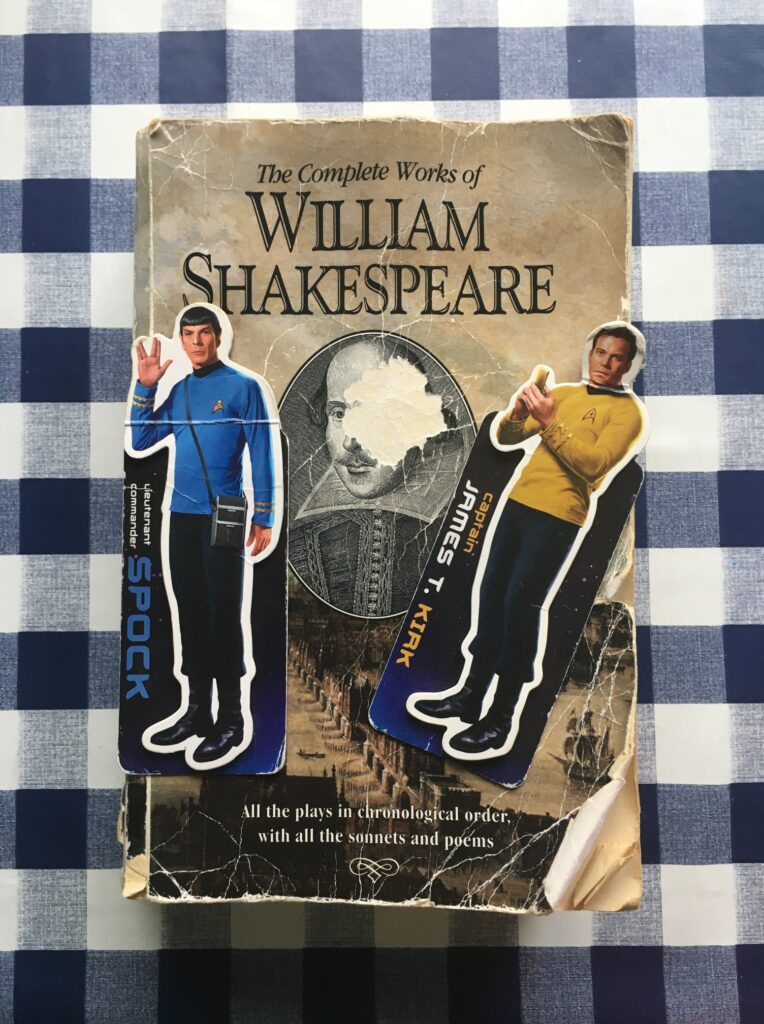

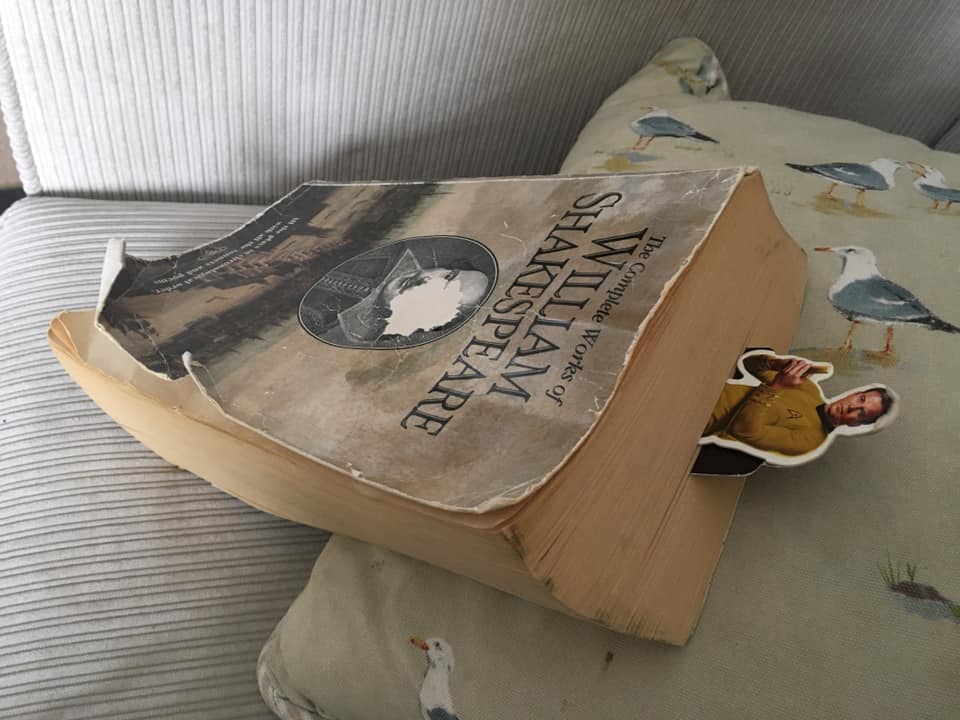

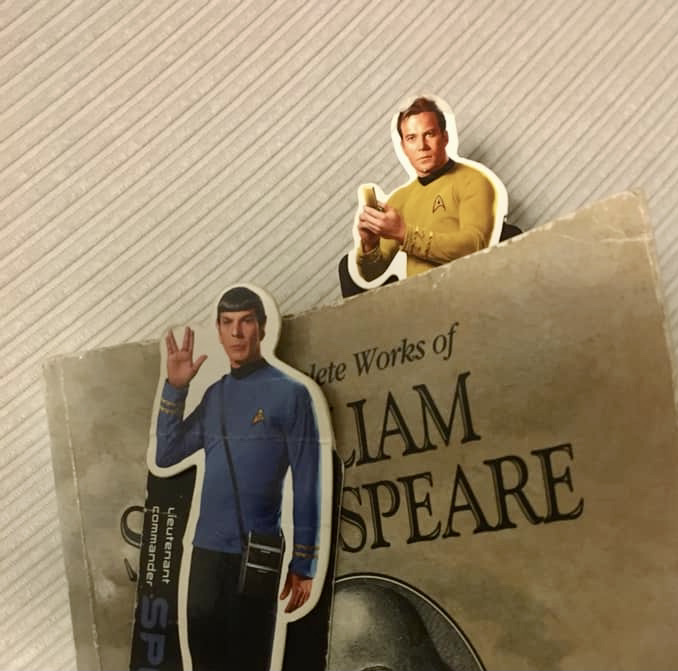

My reading of The Complete Works of Shakespeare was almost at an end. The book (only a paperback) had weighed in at 1250g, and the font was tiny,…

Well, I’d just read all of Shakespeare’s plays and I was feeling extremely showy-offy. And yes, I’d been totally mind-blown or singularly unimpressed and all the stops inbetween….

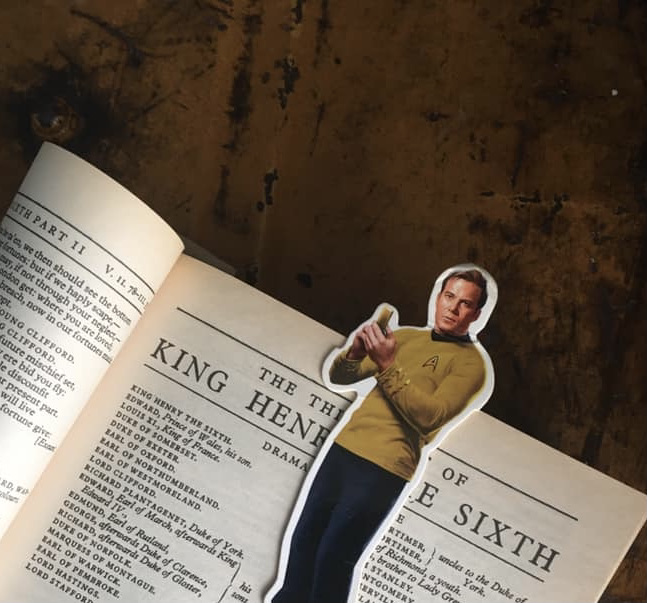

Unbelievably, after nearly six months, I had almost come to the end of the complete works of Shakespeare. That lockdown challenge had proved hard to do sometimes, but…

My book was looking ragged and my Kirk and Spock bookmarks were bent. But I was determined to push on, despite having never heard of a couple of…

By now Shakespeare was all Henried out, so he turned to the ancient world to inspire his next set of plays. With varied results, to be honest, but…

This part of the book had the men taking centre stage. Shakespeare had hit his stride. At least, that’s what I’d heard, and I was interested to see…

My paperback version of The Complete Works of Shakespeare was starting to look properly shabby. I’d bent the cover back a lot, and sat cups of tea on…

I was approaching the halfway mark of my Shakespeare-a-thon, and methought it was time for some top scores. The Big H was coming up, so I was well…

Much Ado About Nothing left me in a good place, so the thought of another comedy coming up was quite welcome. But would it deliver the goods? 19….

It is 1975. I am a teenager, listening for the first time to a protest song by Greg Lake. The tune mesmerises me, the riff stiffens the hairs…

I was cracking on with my stupidly self-imposed lockdown challenge to read The Complete Works of Shakespeare. I’d met a few Henry’s now, and although I knew one…

I’d now hit the stage where I was half enjoying this challenge and half wishing I hadn’t told everyone I was gonna do it. There were expectations, and…

I’d now encountered a few stand-out plays, in my great Shakespeare-reading marathon, so I felt quite buoyed up at the prospect of what was approaching. But then I…

In my quest to read all of Shakespeare from start to finish, I finally made it to plays that I’d heard about and seen on the telly. I…

Full of enthusiasm for my lockdown project of reading The Complete Works of Shakespeare, I wandered blindly on to play number 5. Some time later I stumbled back…

We all remember those drawn out days of the first Covid lockdown, right? I don’t know how you coped, but while other people were learning new languages and…